I just listened to a Wall Street Journal podcast, which featured an interview with a Wall Street Journal reporter. He mentioned the buying opportunity in stocks that is evidenced by a lot of “cash on the sidelines.”

I just listened to a Wall Street Journal podcast, which featured an interview with a Wall Street Journal reporter. He mentioned the buying opportunity in stocks that is evidenced by a lot of “cash on the sidelines.”

This is a contrarian investment idea, and it works like this.

- When investors are nervous, they sell securities, taking comfort in the stability of cash. When they’re enthusiastic, investors invest cash in the hopes that securities will rise.

- All else equal, higher cash balances suggest nervousness/pessimism, while lower cash balances suggest optimism.

- Investing when cash is high, then, is another way to be greedy when others are fearful, and vice versa.

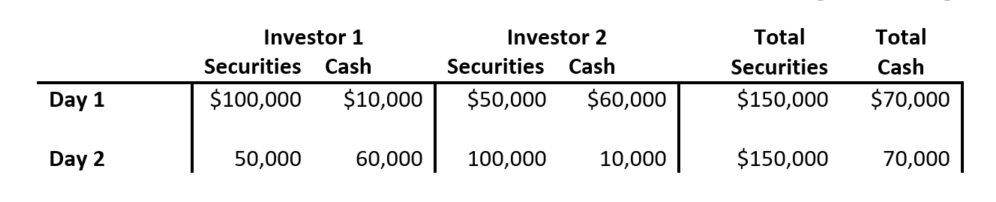

There’s at least one problem with this sort of thinking. In a closed system, there is no net difference in cash. That is, a seller of a stock sells to a buyer, and while the individual allocations change, in aggregate, there is no difference between cash and securities. Here’s a view from the accounting side of things.

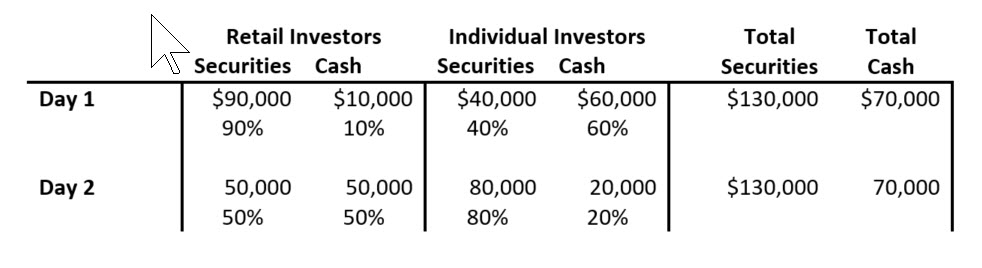

Where this notion does have some validity is when a subset of the closed system is considered. For example, where a retail investor sells to an institutional investor. In the table below, retail investors are considered a group instead of one person.

Now, we can say that individual investors are sitting on the sidelines with increased cash. This represents—as some folks are wont to say—so-called “dry powder,” or cash that can be used to purchase securities, pushing their prices higher. Some might consider this an indication that it’s time to buy.

To make the blanket statement that there is “lots of cash on the sidelines” is nonsense, however. It only works for particular segments of markets.