Imagine asking a small group of people in Conference Room A of a hotel—socially distanced and wearing masks, of course—about their individual driving ability relative to that group. The chances are good that a majority would rate themselves as better than average.

That can’t be, of course; some must be worse than average.

Now, imagine that same group is asked whether each person is a better driver on average than the people in Conference Room A and B. Little do they know that Conference Room B is a gathering of Formula 1 drivers.

I think the average investor imagines him or herself as only competing against the others in Conference Room A. In fact, the chances are good that he or she is forgetting about Conference Room B, which is a gathering of the most sophisticated investors in the world. There is a pretty good chance that the investor you’re selling to and buying from has more information than you.

That’s one of the main reasons underlying our approach of determining a long-term asset allocation and rebalancing to it. We advise only making changes to it as your long-term situation changes. In the meantime, the other stuff is noise and should be ignored. Almost by definition, you can’t know more than your competition.

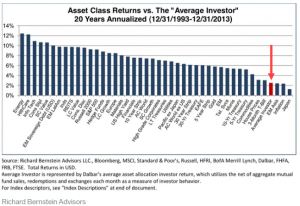

In the 2014 article here, Richard Bernstein, one of the people in Conference Room B, compares the performance of the average mutual fund investor to just about every investment type available, and he displays it in the bar chart featured nearby.

If that’s not enough, also in 2014, Fidelity did a study of returns on its accounts, to see which had done the best. Care to guess which did the best…?

“They were the accounts of people who forgot they had an account at Fidelity.” Read the whole story behind that here.