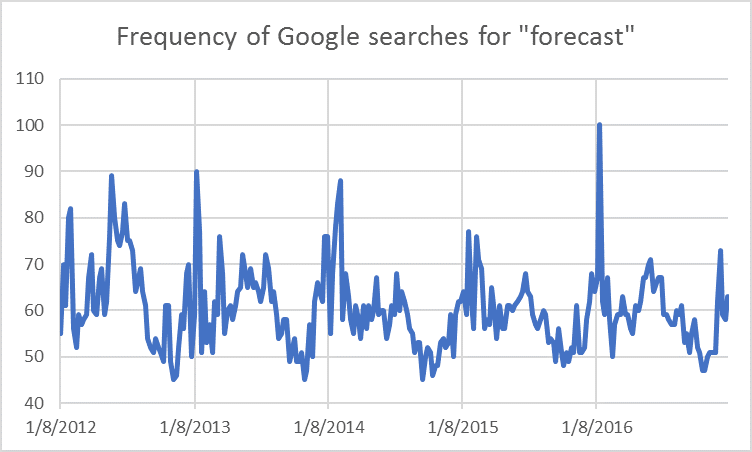

It’s that time of year when Wall Street folks trot out their annual forecasts of markets, economies, and the like. Pictured below is a frequency of Google searches for the word “forecast.” Notice that in each year they peak at the beginning/end of the year.

The problem with forecasts is that they’re almost always wrong. Yes, there are always some forecasts that turn out correctly, just like there are some darts that, if thrown en masse, will stick to the dartboard, and some might even make a bullseye. In a stadium full of coin flippers, there’s likely to be a couple who will flip ten heads in a row, but we don’t say they’re skilled coin flippers.

Every week, this folly is on display with economic indicators. Virtually every Wall Street forecaster will produce a forecast for weekly claims for first time unemployment insurance claims—and every month, for payrolls and others. Forecasts for these will be scattered across a range of values, with the average being called the “consensus.” There’s supposed to be wisdom in crowds, but there isn’t in these crowds, with the consensus only occasionally being right.

Yet, every year, we are drawn to annual forecasts, as witnessed by the chart, above, and clients frequently ask, what do you think the market’s going to do? I think forecasts are a complete joke.

At Strategence Capital, we pretty much ignore forecasts,

other than for their entertainment value.

We think you should, too.

Here is how to make a forecast—other than by just guessing, although I would argue that this process is merely sophisticated guessing.

- Develop model

- Enter inputs to model

- Publish model results

If the modeler gives in to confirmation bias [insert link to approved blog post], then it becomes a four-step process, with the new step #3 being massage model results.

One of the most straightforward things to model is a stock—it’s straightforward, not easy. Here is the model:

That’s it. If you can forecast what the valuation multiple will do (up or down by X%) and what will happen with earnings (up or down by X%), then one just needs to add that to the expected dividend yield to get the total return forecast for a stock. Simple.

It’s a simple concept but incredibly complicated. Think of all the variables that go into it. There’s revenue, expenses, inflation, interest rates, taxes—and each of those can be broken down further.

…and that’s just for a single stock. A stock index is considerably more difficult, and then there’s oil, and gross domestic products, and other complexities.

It’s ridiculously difficult to make accurate forecasts, so one should be very circumspect before making investment decisions based on them. Why? Barry Ritholz, in his blog post titled, The Philosophical Failing of Forecasting, says that,

For investors, one of the biggest risks of forecasting is the unfortunate tendency to stay wedded to predictions. Consider as an example the person who makes a bearish or bullish forecast. The market then goes against them. Rather than admit the error, they double down on the claim. The fear isn’t only that of being wrong, but looking even more foolish as they capitulate just as the unexpected move comes to an end. This fear has caused legions of investors to miss big gains or to sell at the lows after a crash.

You can avoid that sort of behavior by building in rules that reduce these sorts of errors. The line in the sand — aka as a stop loss — is where one must admit a trade isn’t working out, and then unwind it. This helps avoid those sorts of errors. Famed technician Ned Davis once described this issue [by] posing a question: “Do you want to be right or do you want to make money?”

It may be a little late for a 2017 resolution, but if you can work in another one, I’d suggest relying less on predictions and forecasts, if not ignoring them altogether.

Securities offered through LPL Financial, Member FINRA/SIPC. Investment advice offered through Strategence Capital, a registered investment advisor and separate entity from LPL Financial.